Jazz is playing, the sky is dark, and a bright yellow taxi pulls up outside Parthenon Gyros on State Street. “Y’know, I don’t know much about politics. All I know is that we just need a good, hard rain to wash the scum off the streets,” says the man behind the wheel.

It’s not the beginning of Taxi Driver. The man uttering those words isn’t Robert De Niro. He’s Fred Schepartz, local writer by day and driver with Union Cab of Madison Cooperative by night. And the scene is from “You Talkin’ to Me?” — Commie Taxi Drivers in Wisconsin, a DVD extra for Michael Moore’s latest film, Capitalism: A Love Story.

While Commie Taxi Drivers sprang from Moore’s imagination, there’s plenty of creativity inside those yellow cabs. Schepartz is a great example. When he’s not writing books, such as his 2007 novel Vampire Cabbie, he’s taking photographs and editing Mobius, a journal dedicated to literature, poetry and social change.

Without Union, this trifecta of creative output might not be possible. It’s hard to survive as a novelist if you’ve never published a book, and this was Schepartz’s situation for two decades. To pay the rent after college, Schepartz tried secretarial work and furniture sales, only to find himself with a pink slip — not a book deal — a few years later.

Then he heard about Union, a local, worker-owned cooperative brimming with artists, musicians and writers. Twenty-two years and several novels later, he’s still driving for Union. Like many fellow drivers, he’s discovered that you don’t need an MFA degree to make art, and that creativity and cab driving go hand in hand.

Of course, this combination doesn’t work for everyone. Cab driving in Madison requires a high tolerance for drunk people and the ability to stay cool when other drivers are texting and tailgating on the Beltline.

Plus, not every cab company offers a structure or vision like Union’s. Its mission statement includes a commitment to paying workers a living wage, whether they drive cabs, crunch numbers or clean toilets. For drivers, pay is based on a commission that’s a percentage of customer fees. The more hours drivers log, the bigger cut they get.

“Over the last 30 years or so, median wages for most working Americans have dropped, but the way Union Cab is set up, your real wage actually increases. And this helps the artistic life if you don’t have to work 60, 80 or 100 hours a week just to eke out a living,” Schepartz says. “And when you leave your shift, you don’t take your work home with you. To make art, you need a lot of time to think.”

Culture club

For Union Cab drivers, contemplation can even happen on the job, while waiting at an airport or a stoplight. For Mark Adkins, leader of Subvocal, a psych-folk band formed at Union Cab, an epiphany at the corner of State and Gilman streets led to one of his most memorable songs, “11303.”

“I saw this student walking by who was very pretty, except her nose was missing. I wondered how she dealt with her lot in life, and I began thinking about how people wear these different masks,” he recalls. “I came up with the song’s first line, ‘I see nothing but sorrow walking down the street,’ and I realized I was writing down feelings about my brother, who’d recently committed suicide. It was a real turning point.”

The album containing “11303,” Nikkis Room, was a turning point as well, winning Subvocal the 2005 Madison Area Music Award for best CD.

Good pay and ample downtime aren’t the only reasons creative people flock to Union. The co-op takes pride in its nontraditional philosophy about work. As a result, its culture isn’t typical.

“People are exactly who they say they are there, and it’s a very comfortable place to work because you don’t have to worry about what other people think,” says Jai Ingersoll, Union alum and vocalist for local goth-tronica group Sensuous Enemy. “I have tattoos and piercings and red hair, but it didn’t matter there. A lot of other places it would.”

Plus, if you talk to Union drivers at length, you’re likely to hear them refer to fellow worker-owners as family, not coworkers. As Adkins puts it, “We’re all writers and musicians and politicos, rebels and radicals and misfits. But even those of us with crappy attitudes will still get out of the car to fix your flat on a snowy day.”

This isn’t because Union workers are more compassionate than others; it’s a function of an environment that eschews competition and promotes empowerment, Adkins says. This type of atmosphere can also help talented people truly pursue their gifts, whether it’s music, metalworking or mime.

John McNamara, the co-op’s marketing manager, says a humane work environment simply encourages people to do their very best, whether it’s in the office, in a cab or at their after-work pursuits.

“We want people to like coming to work, not feel chewed up and spit out, which is the case at many companies. And because of the camaraderie that exists here, there’s a natural tendency to share and collaborate,” he says. “We work on teams and solve problems together. There’s not a lot of selfishness here, and that way of doing things spills over into other parts of people’s lives.”

McNamara credits much of this outlook to the zeitgeist of the 1970s, when Madison flexed its creative muscles in unprecedented ways. “People were really questioning the status quo and coming up with positive ways of changing the world,” he says. “The Union Cab people were part of this, along with WORT, the Willy Street Co-op, the Mifflin Street Co-op and Commonwealth Development.”

Problems plaguing the cab industry were troubling for drivers and consumers alike, he adds.

“Everything was being done on the cheap back then. Vehicles were unsafe, and drivers were very poorly paid. That translated into poor morale and poor customer service.” And that’s one thing Union’s founders set out to change.

Creative folks soon caught wind of the co-op’s flexible schedules, which could easily accommodate a band’s cross-country tour or a two-month writing sabbatical, and began to fill the Union’s ranks. Pretty soon, Butch Vig, who would go on to found Smart Studios and the band Garbage, was driving a Union cab. So was Michael Feldman, who now hosts the comedy and quiz show Whad’Ya Know?, which is heard on public radio stations across the country. Local author and historian Stu Levitan and Latin-jazz icon Tony Castañeda followed, along with many others.

Feldman, who drove for Union from 1981 to 1983, after quitting his first radio show, says unemployment led him to the co-op, along with its reputation for hiring creative individuals.

“They were hiring people like actor cab drivers and writer cab drivers, and they took me because I was a minor celebrity. They thought it would be good for business, but I was a terrible cab driver.”

Though Feldman doubted his cabbie skills, the gig led to something useful: a new public radio show. “We taped radio bits in the cabs and called it The Dispatcher,” he says. As a dispatcher wrangled cabs, “I’d be trying to break in with a question, like ‘What caused the extinction of the dinosaurs?’ We’d tape that and put it on the air.”

Rearview visionaries

Since Union has more than 200 employees, chances are good that an artsy new hire will already know a few other workers from gallery night or the local concert scene. Once these folks find each other, collaboration ensues.

Take longtime cabbie Kelly Burns Gray. A visual artist, she made sure a new CD of music by Union employees past and present came to be. Some of this do-good spirit stems from her personality, but another motivation is thanking Castañeda, who mentored her on some of her first drives.

“One of the things he trained me on was how to hold a coffee cup between my legs and use my lap as a plate. That experience sealed the deal,” she recalls.

Gray had watched Adkins put together Rearview Visionaries, a disc of Union cabbies’ original music, in 2002, so she knew the project could be done if she connected with the right people. With songs by Model Citizen, Wayside, Subvocal and others, the album’s still talked about among cabbies, and many seemed eager to create a follow-up. According to Steve Pingry, cellist for Subvocal and the Getaway Drivers, the original idea was to create a Rearview Visionaries boxed set, so a second CD would mean that the project was two-thirds complete.

After soliciting submissions on Facebook and through the grapevine, Gray got in touch with local musician and fellow cabbie Lonnie Wild, who paid for duplication of the new CD. Meanwhile, Smart Studios’ Mike Zirkel volunteered to master it. The final product debuted in January, featuring tracks by Sensuous Enemy, the Stellanovas, the Getaway Drivers, Castañeda and many others. In addition to spinning in many cabbies’ cars, it won a Madison Area Music Award this spring.

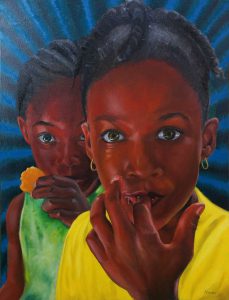

Meanwhile, Kristin Forde, a visual artist, theater person and Union cabbie of six years, has been organizing art shows with a purpose similar to the CDs’: to highlight the co-op’s creative talent. The first show, featuring political posters, photography, blown-glass mixed-media pieces and more by 10 Union Cab artists, took place last summer at the Gallery at Yahara Bay Distillery. Another will take place at the gallery July 29 through Sept. 24 of this year, with an opening reception July 30.

Forde, a former middle school teacher, credits cab driving for sparking a personal artistic awakening, so organizing a show is the least she can do to give back.

“Cab driving has opened up my creative life tremendously,” she says. “There’s something about being in constant motion, with the scenery always changing, that’s important to the photographs I take.”

And this sense of moving forward, making progress toward destinations physical, political, psychological and spiritual, is crucial to what Union stands for. It’s only natural that cabbies show off the values they’ve taught and learned at the co-op.

“The co-op model attracts people who are interested in an alternative way of life, one that’s very participatory and has a strong creative element,” Forde says. “Those of us who work at Union own it, too, so it’s up to us to make sure it remains this unique place that nurtures things the greater society doesn’t always value: individuality, creative expression and, of course, union.”

Randy Brandner had a problem. The Merrill Chamber of Commerce had outgrown its office space, and people were looking to him, its president, for answers. Luckily, he found a solution with the help of the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s

Randy Brandner had a problem. The Merrill Chamber of Commerce had outgrown its office space, and people were looking to him, its president, for answers. Luckily, he found a solution with the help of the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s  When Continuing Studies’ Barbara Nehls-Lowe learned Tagalog, she was living in the Philippines, serving in the Peace Corps. Then she returned to the U.S., where learning a language was much harder. For years she studied Spanish, which is useful for her work with the Wisconsin HIV Outreach Project, but she never found her way. Things changed when she signed up for Continuing Studies language courses.

When Continuing Studies’ Barbara Nehls-Lowe learned Tagalog, she was living in the Philippines, serving in the Peace Corps. Then she returned to the U.S., where learning a language was much harder. For years she studied Spanish, which is useful for her work with the Wisconsin HIV Outreach Project, but she never found her way. Things changed when she signed up for Continuing Studies language courses.

Since forming five years ago, the Minneapolis guitar-and-drums duo Birthday Suits have played hundreds of explosive shows, many in Madison. But until recently, they’d only recorded one other full-length, a mere 15 minutes’ worth of material.

Since forming five years ago, the Minneapolis guitar-and-drums duo Birthday Suits have played hundreds of explosive shows, many in Madison. But until recently, they’d only recorded one other full-length, a mere 15 minutes’ worth of material.