It’s easy to equate the term “paper arts” with grade-school crafts such as paper dolls and papier-mâché piñatas. Thankfully, Aries Tjhin’s new exhibition at the Project Lodge, on display through Feb. 20, is designed to put these images through the shredder, both literally and figuratively.

Tjhin, a 2008 graduate of UW-Madison’s printmaking MFA program and a member of the Milwaukee-based White Whale Collective, carves miniature murals out of paper and cardboard. The process is a meticulous one that involves a steady kitchen table and some impressive skill with an X-Acto knife. From afar, many of the pieces resemble collages of paper doilies and snowflakes, but up close the dark truth comes out: They’re hacked-apart pieces of fairy tales and children’s storybooks, deconstructed, rearranged, and butched up with spray paint.

“The show is about stories—and different kinds of stories—especially stories I’ve read throughout childhood and that flash through my head at these really random times,” says Tjhin. “The way the pieces are made forces you to look at the stories in detail and study the nuances of how they’re made.”

The centerpiece of the installation—a long, horizontal piece called “Hieroglyphics”—fills the gallery’s west wall with glimpses of African folk tales. Familiar figures such as jungle monkeys and a guy who just might be Anansi The Trickster peek out from from a lattice of carved leaves and feathers, vanish into a haze of geometric abstraction, then re-appear in different forms throughout the piece. Some areas of the composition are made entirely of black paper, while others incorporate layers of cardboard and paint, suggesting the many voices and layers that go into the telling and retelling of a story.

Across the room, a piece titled “Door” acts as a portal to an imaginary landscape of horses, clouds, and ninja-like figures that are strung together with a vine straight out of Jack And The Beanstalk. A more abstract piece called “Untitled Yellow” seems like the introduction to a storytelling session—the kind that begins with the incantation “It was a dark and stormy night.” A sky of precisely carved shapes, dusted with tiny yellow paint drops, seems to be breaking apart on a misty evening. Whether it’s a hopeful or ominous story is up for debate: The clouds and stars have been sliced apart and collaged, as if the world is taking a new shape—or history is caving in on itself.

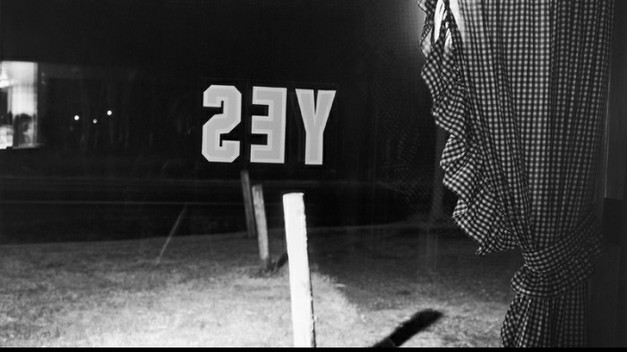

Pieces of text often come disguised as debris–candy wrappers, discarded receipts, fading patches of graffiti–but they’re still saying something. It’s just a question of what. For photographer Lewis Koch (who speaks this Saturday afternoon at Rainbow Bookstore Co-Op), these letters, numbers, and symbols spell out poems. They might not form tidy stanzas or couplets, and they might not rhyme, but they share the spirit of Surrealism that has fascinated poets such as John Ashbery and Allen Ginsberg and free-jazz musicians like Sun Ra. They speak to us in a language that’s alien to our sense of reason, but familiar to our emotions and even our memories.

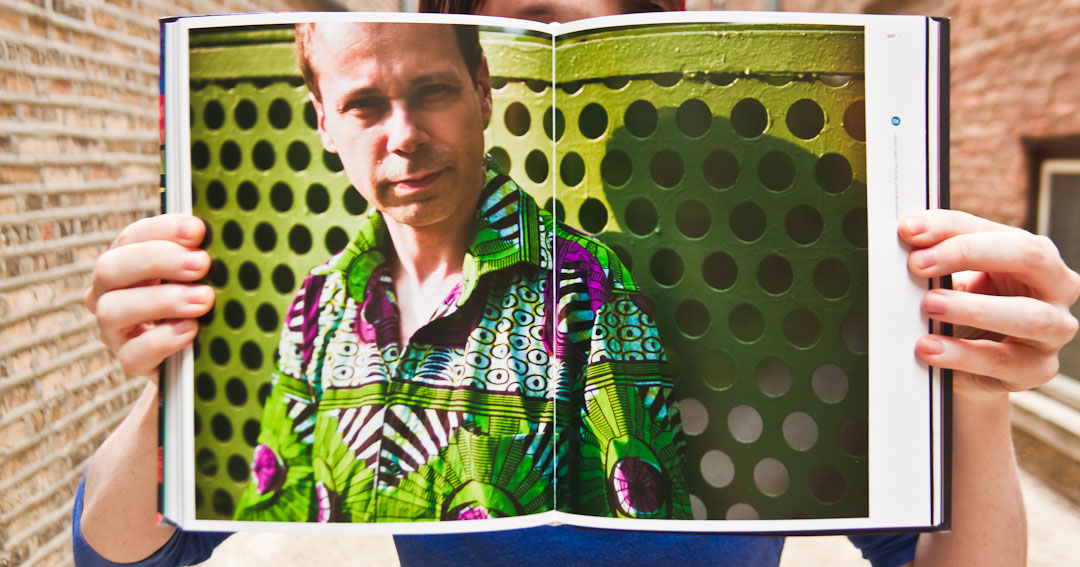

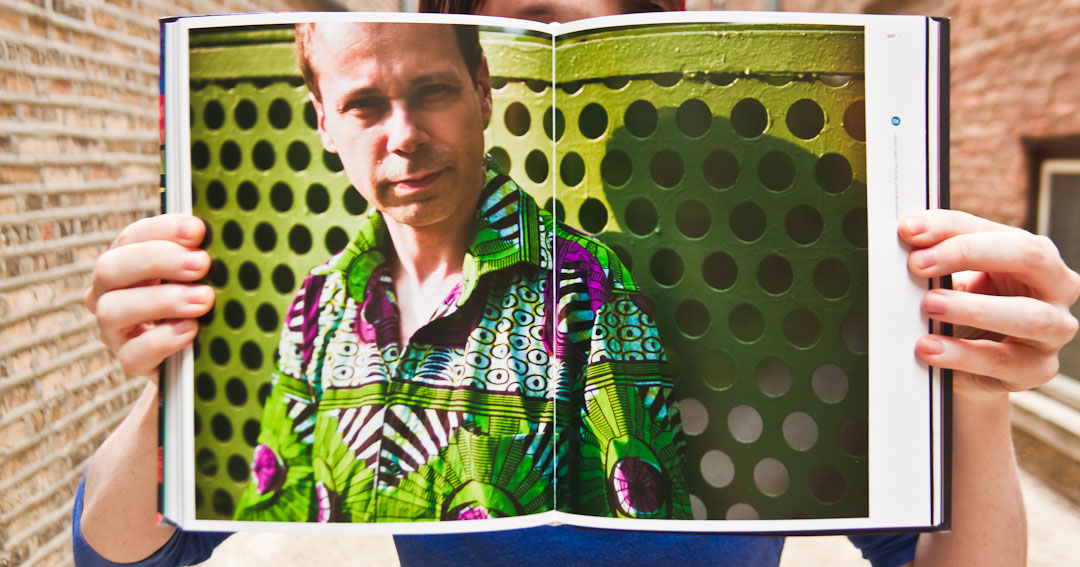

Koch’s new book, Touchless Automatic Wonder, a collection of what he calls “found text photographs from the real world,” creates a poem that’s both miniature and epic. Though these images contain just a handful of words, they say a lot and ask even more. They also represent nearly three decades of observation and creation by the Madison-based artist, whose work has made its way into the permanent collections of the Whitney and the Metropolitan Museum Of Art and appeared in exhibitions in New York, London, Seoul, and beyond.

The book begins with a black-and-white print of a window, viewed from the inside of a building. Plastered on the glass is the word “yes,” which appears to float above the street outside. A few pages later is a long-division problem, spelled out in sticks–or pretzel sticks, perhaps–on a table peppered with napkins and coffee cups. Other words and letters pop up like guests at a surprise party: The word “dream” (emblazoned on some large, decaying object) hides behind a chalkboard of children’s drawings; a broken record surfaces in a field, among the unruly leaves and flowers. A painting of a lady revealing her garter points at the word “almost,” while a television with a man waving his finger reminds everyone to “wear suspenders,” as if neglecting to do so is a very serious transgression. Meanwhile, a deserted car lot sprouts four signs from its cracked concrete, all of which say “OK,” even though business clearly isn’t booming.

What’s most fascinating about these photos, however, is that they’ll likely mean something different to each person who sees them, dredging up a unique combination of memories and associations. In the introduction to the book, Koch says it’s the images’ fragmented nature that creates a “sometimes deliberate, sometimes accidental account of one’s life.” But rather than reading them like a novel, they can be read like a diary, a riddle, or even a dream.