Carolina Chocolate Drops knows a thing or two about blending in. On the cover of the trio’s 2010 album, Genuine Negro Jig, Rhiannon Giddens makes camouflage out of a bright-red dress. Draped on the sofa like a blanket, she matches her surroundings (a red velvet curtain and Oriental rug) so well that she almost disappears. That’s no small feat.

Maybe she’s remembering the old days of the band’s home base of Durham, North Carolina, where until the ’60s, black faces occupied the backs of buses and the margins of their local community, even though they’d created a thriving center of industry, culture, and especially music.

Or maybe she’s channeling the spirit of writer Mary Mebane, who likened her 1930s Durham childhood to an elaborate game of dress-up. Mebane described this Durham as a place where “black skin was to be disguised at all costs” and where those with the darkest faces drowned their insecurities in makeup and whiskey.

Though Appalachian tunes have become the music of all Americans, there’s another truth lurking in the shadows: the story behind the music has been whitewashed.

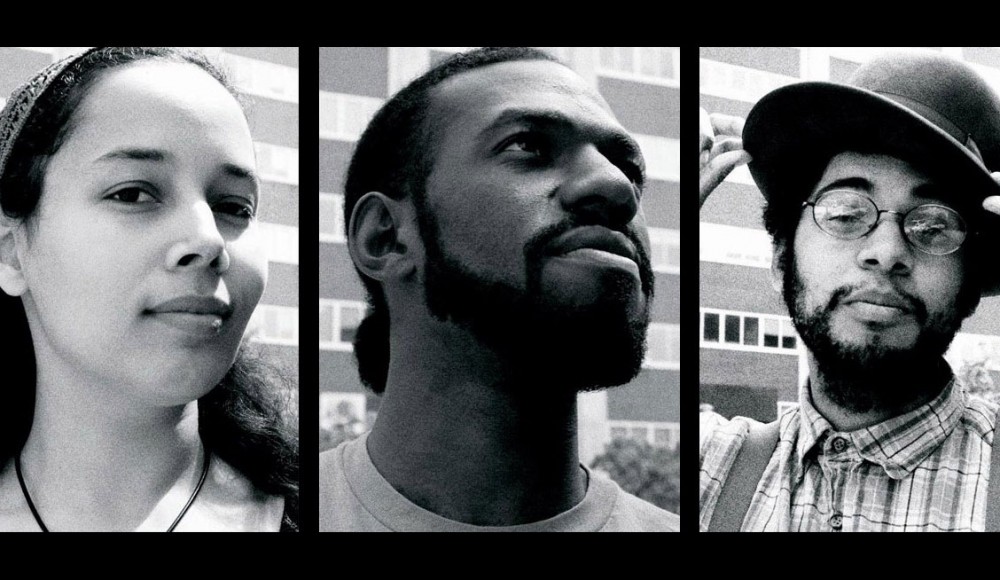

So perhaps standing out is an even larger feat for Giddens and her bandmates, Dom Flemons and Justin Robinson. They can’t help it, given their musical chops, but they don’t just accept it. They embrace it. And they get their gusto from the ghosts of North Carolina’s past, the black folks who pioneered much of the Appalachian music that launched the careers of white guys like Bela Fleck, the New Lost Ramblers, and the Avett Brothers.

Surprisingly, it was Fleck and the Ramblers who helped Giddens, Flemons, and Robinson find one another at the 2005 Black Banjo Gathering in Boone, NC. The three expected to learn about the instrument’s African and African-American roots, not come away with a globetrotting ensemble and a record deal.

The timing must have been just right. Fleck had recently returned from an African tour, and Mike Seeger of the Ramblers had left New York for a southern sojourn. Flemons traveled all the way from Phoenix just to learn from them. But it was an 86-year-old fiddler named Joe Thompson who sealed the deal, transforming three wandering souls into a tight-knit ensemble.

Now 91, Thompson is thought to be the last living performer from the golden age of Piedmont string bands. In the early 20th Century, he and his family were playing socials and square dances for black and white families alike. At the time, it was one of the rare instances where the racial divide softened, if only for a few hours.

Many people are familiar with the white fiddle-and-banjo music of the southern Appalachian region, but the Piedmont tradition is slightly different. Unlike other Appalachian music, it gives the leading role to the banjo, which sets the tone and tempo of the tunes. The fiddle tends to come second, providing backup along with instruments such as the jug and spoons. This unique combination was pioneered by families of black musicians. Although the banjo was created in the USA, it was inspired by a few lute-like West African instruments. Banjo music was often passed from one black family to the next, and it eventually made its way to other ethnic groups. Until the early 20th Century, young white musicians usually befriended an older black musician if they wanted to learn it.

Learning the banjo also helped the Drops find its identity as a band. Though the group is an old-time string band steeped in Piedmont’s unique blend of folk and blues, it’s a melting pot of other influences as well: some hip hop here, some bluegrass there, with rock and jazz essences filling the gaps. But the three musicians didn’t meld together until Thompson entered the picture.

Somebody had to figure out how to integrate the styles of Giddens, an opera singer with a soft spot for Irish jigs and jazz, with those of Robinson, a classically trained violinist, and Flemons, an Arizona native with a background in folk, jug bands, and old-fashioned country and blues. A Piedmont fiddler through and through, Thompson decided that the best way was to teach them to accompany each other in music and in life.

“We’d go down to his house on Thursday nights and learn how to back him up,” Flemons says. “He’d tell us about some of the older ways of [Southern] living, things like tobacco auctions and frolics, which are square dances in the black community. We really learned about the social functions of the music.”

Pretty soon the band was swapping melodies and instruments, do-si-do style. Now Robinson takes the lead on fiddle, adding banjo, autoharp, and jug as needed, while Flemons lends his skills on various banjos, plus the jug, quills, and harmonica. Giddens plays fiddle, banjo, and kazoo when she’s not wowing the crowd with her vocals.

The audience has added instruments to the lineup too. One fan gave Flemons a set of bones, which also spice up the rhythm of minstrel songs, zydeco, and bluegrass.

“She insisted that I learn how to use them, then showed me how to play them,” he says. “There have been a lot of interesting and wonderful experiences where people have shared songs, instruments, and memories with us. For some reason, our music has opened that up inside of them. Being able to do that is truly amazing.”

Though the group’s goal is to make great music and build a bit of community, it comes with a side of history, especially at its live shows, where Carolina Chocolate Drops is interested in telling the history that history books left out. The trio isn’t breaking out Howard Zinn’s books on stage, but it’s telling it like it is: black people pioneered much of the traditional folk music that spawned country songs. And the banjo wasn’t invented by Bo Duke and The Balladeer. It evolved from several types of African lutes, thanks to the ingenuity of slaves — a fact that banjo players themselves often are surprised to learn.

In other words, though Appalachian tunes have become the music of all Americans, there’s another truth lurking in the shadows: the story behind the music has been whitewashed. We tend to remember the white banjo students but not their black teachers. As a result, much of tradition’s richness is buried, along with the bones of those who played the minstrel shows of the 1880s and the hoedowns of the 1920s and ’30s.

Carolina Chocolate Drops makes music that breaks down cultural barriers and brings together people from various walks of life, but it’s making those black musicians and teachers stick out — in a good way. It’s also helping them gain their rightful place in history and in the imaginations of those listening to the music today.

This theme of rewriting history is heavy one moment and lighthearted the next, much like the songs of Genuine Negro Jig. At least half of the album is good, old-fashioned hoedown fare. There’s hooting and hollering and crazy kazoo solos. There’s more banjo than the Dukes of Hazzard theme song and plenty of material for stomping, swinging, and square dancing.

The other half has some frank messages: advice on how to treat a cheatin’ man and exorcise one’s inner demons. It’s the kind of stuff that gets you talking after passing out from moonshine and dancing. You can’t help but get to know your neighbor.

This is a novel concept for people who spend most of their time on Facebook and iPhones. Yes, the Internet is great at bringing people together, but you can’t dance with it. That’s why Carolina Chocolate Drops blends the whimsy of eras past with the stuff that makes people human today: getting drunk, making out, showing off, and screwing up.

Flemons says that the group marries old and new with the West African concept of Sankofa, which means “go back and fetch it.” It takes good ideas from the past, brings them to the present, and gives them new life.

“We’re not trying to bring the old times back, but we’re using them to help people enjoy themselves,” he says. “Building community by getting people to sing and dance together at a concert makes sense in the modern world.”

But there’s more to it than that. They’re creating something new as well.

Most recently, the music opened the doors of Nonesuch Records, the label that the Magnetic Fields, Brian Wilson, and David Byrne call home. This, in turn, unlocked a Pasadena mansion that once belonged to President Garfield’s widow — and where producer Joe Henry now lives. It was the perfect place to record an album built upon American history.

These sessions led to a haunting rendition of Tom Waits‘ “Trampled Rose” and a fiddle-hop take on Blu Cantrell‘s “Hit ‘Em Up Style.” On the latter, Giddens’ vocals create shivers as she alternately sets the track on fire with her fiddle. Underneath, Flemons’ beat boxing conjures the streets better than a cranked-up bass and a set of chrome rims. Then on the old Charlie Jackson tune “Your Baby Ain’t Sweet Like Mine,” the band traces the blues back to its roots and gives them a Vaudevillian twist, while the Carolinian standard “Trouble in Your Mind” creates the insanity of which it warns with an out-and-out hootenanny. It’s hardly the way to blend in with the crowd.

Flemons says that the album is more of a genre-bender than the band’s earlier releases, but don’t expect Carolina Chocolate Drops to change its tune anytime soon.

“We’re proud to be who we are: an old-time black string band,” he says. “We don’t need to turn into a ’60s girl group or a hair band to stand out.”