Pieces of text often come disguised as debris–candy wrappers, discarded receipts, fading patches of graffiti–but they’re still saying something. It’s just a question of what. For photographer Lewis Koch (who speaks this Saturday afternoon at Rainbow Bookstore Co-Op), these letters, numbers, and symbols spell out poems. They might not form tidy stanzas or couplets, and they might not rhyme, but they share the spirit of Surrealism that has fascinated poets such as John Ashbery and Allen Ginsberg and free-jazz musicians like Sun Ra. They speak to us in a language that’s alien to our sense of reason, but familiar to our emotions and even our memories.

Koch’s new book, Touchless Automatic Wonder, a collection of what he calls “found text photographs from the real world,” creates a poem that’s both miniature and epic. Though these images contain just a handful of words, they say a lot and ask even more. They also represent nearly three decades of observation and creation by the Madison-based artist, whose work has made its way into the permanent collections of the Whitney and the Metropolitan Museum Of Art and appeared in exhibitions in New York, London, Seoul, and beyond.

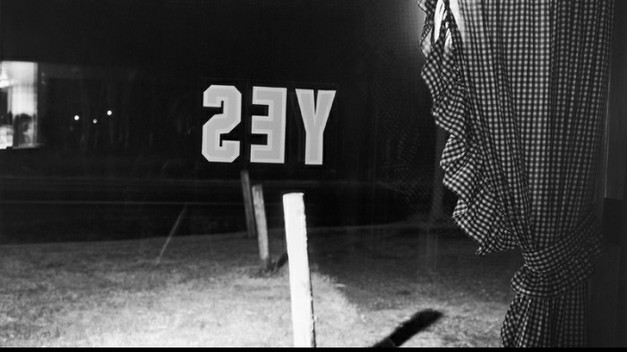

The book begins with a black-and-white print of a window, viewed from the inside of a building. Plastered on the glass is the word “yes,” which appears to float above the street outside. A few pages later is a long-division problem, spelled out in sticks–or pretzel sticks, perhaps–on a table peppered with napkins and coffee cups. Other words and letters pop up like guests at a surprise party: The word “dream” (emblazoned on some large, decaying object) hides behind a chalkboard of children’s drawings; a broken record surfaces in a field, among the unruly leaves and flowers. A painting of a lady revealing her garter points at the word “almost,” while a television with a man waving his finger reminds everyone to “wear suspenders,” as if neglecting to do so is a very serious transgression. Meanwhile, a deserted car lot sprouts four signs from its cracked concrete, all of which say “OK,” even though business clearly isn’t booming.

What’s most fascinating about these photos, however, is that they’ll likely mean something different to each person who sees them, dredging up a unique combination of memories and associations. In the introduction to the book, Koch says it’s the images’ fragmented nature that creates a “sometimes deliberate, sometimes accidental account of one’s life.” But rather than reading them like a novel, they can be read like a diary, a riddle, or even a dream.