Composer John Cage, the man responsible for the world’s first song that consisted entirely of a man sitting idly in front of a piano, adored randomness in its many forms. So did choreographer Merce Cunningham, one of Cage’s most important collaborators and his longtime boyfriend. Though both men were pioneers of avant-garde art and teachers at the super-experimental Black Mountain College (also the home of artists Josef and Anni Albers, Willem De Kooning, and Robert Motherwell), neither focused on visual art. It’s their shared love of randomness that unites the visual works the Madison Museum Of Contemporary Art has assembled in Cage And Cunningham: Chance, Time, And Concept In The Visual Arts, on display through May 9.

A lack of structure and formality becomes the show’s common thread, forging connections among pieces from the Bauhaus school, the conceptual art movement, and the ’60s “happenings” of the New York City counterculture. It’s not always clear how exactly the works should be associated with Cage or Cunningham (with some exceptions); perhaps the show’s curator wanted it that way.

Sol LeWitt’s 1991 etching “Vertical Not Straight Lines Not Touching On Color” consists—surprise, surprise—of a smattering of white vertical lines, some more squiggly than straight, on a black rectangle of background. Each line is pencil-thin and hairlike, and several of them veer so close to one another that they appear to touch, despite what the museum’s notes about the piece say. As the title suggests, this piece is more about absence than presence. LeWitt’s idea becomes more important than the execution of his idea, illustrating what conceptual art is about.

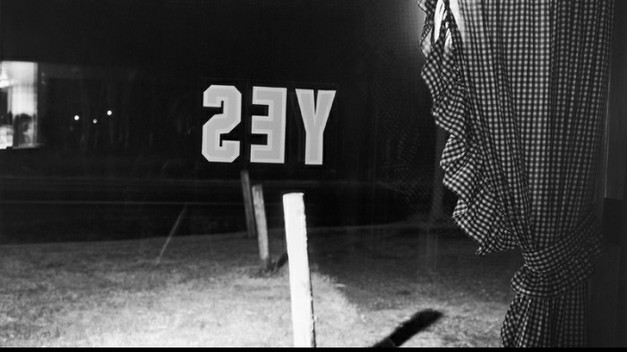

Cage And Cunninghan also offers a roadmap for understanding how things such as noise and found sounds have become the musical staples they are today. Two pieces by George Maciunas show how the multimedia Fluxus movement of the ’60s, a precursor to the modern noise-music craze, among other things, used games and chance to create a new set of rules for art and music. “Single Card Flux Deck” displays a deck of 52 cards, all of which are spades. Three sets of four tens are turned up, as if to illustrate a winning hand in a game from another culture—or another dimension. It’s as simple as it is mind-boggling.

“Fluxshop Sheet,” on the other hand, is both a game and an advertisement for one. A poster made of black ink on old, yellowing paper that gives it an old-timey feel, like a wanted poster in a saloon, it contains two blocks of text, one horizontal and the other vertical, that spell out a manifesto (or something like one) for such Fluxus artists as Yoko Ono, Ay-O and George Brecht. It spouts activist terms like “nonprofit” and “nonparasitic” while an old-timey cartoon character entices viewers with “games, gags, jokes, kits.” Sixteen faces at the bottom of the piece hold letters on their tongues (or perhaps their chins) that spell “flux orchestra.” It’s yet another example of how Cage and his followers blurred the lines that separate literature, visual art, and music.

“Weather-ed II,” a color photoetching by Cage himself, ventures into the territory of meteorology. With abstract lines rendered in grays, blues and purples, he doesn’t examine the raindrops and lightning but the randomness of weather patterns, from the way they take shape to the way we interpret them. These lines are framed by two boxes that function as windows for watching one storm happen and another one brew. At the same time, they’re a bit like music players as well, with Cage’s lines forming shapes that look suspiciously similar to sound waves. Perhaps this is a chance resemblance, but if so, it’s one he would probably have appreciated.