In October 1992, nearly 1,000 music fans were arrested at a rave in Milwaukee’s Third Ward, sparking a controversy about electronic dance music and its purported influence on young people. In those days, DJs spun records imported from Europe as crowds in warehouses danced until sunrise, glow sticks raised.

After the raid, promotional word about raves spread quietly. Flyers led to a hotline number, then a recorded message, then a secret meeting spot, where you’d get a map to a far-flung barn or campsite. The stealth gave the movement a thrilling quality. But as the media hyped the dangers — designer drugs and fire hazards — musical trends changed, sending EDM deep into the underground.

Twenty years later, you can still attend a “rave” in Wisconsin, but it will be easy to find. A promoter will tweet about it, and it will take place at a public venue like the Alliant Energy Center, where on April 13, the electronic artist Bassnectar will crank out party bangers and inventive remixes of tunes by dance-pop darling Ellie Goulding and gypsy punks Gogol Bordello.

Many of the genre’s visual elements are the same as they were in the 1990s, but they’re bigger and brighter, with laser lights, fog and projected images that make mouths gape as thousands of bodies writhe to the rhythms of dubstep, electro house and other varieties of EDM. If you go to the Bassnectar show, look for a crowd writhing ecstatically in a stew of bleeps and bloops, waving their hands amid a miasma of confetti.

Dance till dawn

EDM’s popularity is booming. After performing mash-ups at UW-Madison’s student union five years ago, Girl Talk now fills the Alliant Energy Center’s 6,000-capacity Exhibition Hall. Bassnectar will likely do the same. He played the tiny King Club in 2007 and the Majestic Theatre in 2009.

Some fans who’ve experienced both rave scenes swear they’re similar. Matt Fanale, a local music fan who DJs under the name Eurotic, says a new generation of concertgoers wants to dress in neon and dance till dawn. To him, this is evidence that music trends come in 20-year cycles, and that the motivation to party is the same as it ever was.

“At rock shows, you’re singing and screaming along, but you’re not necessarily dancing,” he says. “With a DJ, you don’t have to watch what’s onstage. You can pay more attention to the other people who are there and feel a real connection to them for a few hours.”

Fanale suspects that the sluggish economy has fueled attendance at live electronic shows. “With the world as depressing as it has been lately, people want to lose themselves with thousands of others. It’s more fun to be happy than angry,” he says.

The paradoxically isolating nature of social media also plays a role, according to DJ Nick Nice, who helped launch the Midwest rave scene in the early 1990s after spinning records at Queen, a Paris club where David Guetta curated the music. “Facebook is such a solitary experience. It’s basic human nature to want to be social, and listening to music with thousands of other people reminds you that you’re not alone, even when the world seems to be falling apart,” he says.

Though these concerts can draw huge crowds and kindle a sense of connection, they can also create rifts. Madison resident Vinnie Toma loves to DJ. He’s built a career around it since 1998. But when he thinks about nuevo-raves, his heart sinks. Though many who attend these shows crave connection, this quest, for some, spirals into escapism.

“In this country, during times of economic downturn, you see the younger generation turn to music that’s a little less thoughtful,” he says. “Kids who are in college right now, or even several years out, there aren’t as many opportunities, and they’ve racked up tons of school debt. It can fuel a lifestyle that’s all about partying and pushing [difficult] emotions away.”

Local DJ Wyatt Agard says these big shows sometimes don’t feel like raves at all. In the early days, raves revolved around ideals like unity and respect. Partygoers hoped to find themselves as they swam through rooms of trance, house and techno — or at least that’s how they remember it.

“A lot of the [current] shows feel like concerts, not parties,” he says. “At raves, not everyone faced forward. There was this cyclical feeling as people moved around the room. Many of the shows now, people face forward, toward a stage, and stay put for hours.”

In other words, people tend to surround themselves with friends rather than explore. That can lend a rock vibe to events, especially at shows that incorporate rock sounds. “The Rusko show at the Orpheum [on Feb. 25] was a lot like a rock concert,” Agard says. “People were moving on beat but not dancing, and if you examine the music theory behind it, dubstep looks a lot like rock, except with electronic instruments.”

EDM goes mainstream

Despite EDM’s popularity, it didn’t gain much mainstream acceptance in the 1990s. Its sounds filtered into the public consciousness from underground. Nowadays, though, its key elements — synths, samples, sequencers — drive songs by Top 40 artists like Lady Gaga, Rihanna and Ke$ha, as Jay-Z raps atop Daft Punk tracks.

Daft Punk’s influence can’t be understated. The French duo, whose songs include “One More Time” and “Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger,” have transformed disco beats into music that sounds thoroughly modern, and their music can be found in the soundtrack to Tron: Legacy, videogames like Just Dance 3 and nearly every corner of the web. The group played one of their first live performances at a Wisconsin rave in 1994, notes Chris Vrakas, a Milwaukee-based DJ and event coordinator for Chicago-based concert promoter React Presents.

Daft Punk also proved that live EDM could be more than a DJ spinning records or tickling a computer keyboard. The group donned space-ready helmets on their 1997 tour, which spurred other EDM artists to bust out the theatrics. Glitch-hop act Pretty Lights crafts visual spectacles incorporating colorful lights and 3-D images, and Deadmau5 has designed his own whimsical headgear with the help of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop.

Ryan Parks, a local EDM fan who hosts WORT’s “Something Wonderful” on Monday Nights, says Deadmau5’s live show is particularly buzzworthy.

“He blew me away, and I’ve seen hundreds of concerts: Paul Oakenfold, the Chemical Brothers, you name it,” Parks says. “It was a multi-sensory experience, where the visual aspect worked in tandem with the sound. The cube he was sitting in would broadcast these 3-D images on the walls, more and more of them as the night went on. Pretty soon, they were popping up everywhere and reflecting off his mask as they pulsed along with the beat.”

These abstract effects attract various kinds of fans, from music-loving Gen X-ers like Parks to kids barely old enough to drive. The under-30 set tends to dominate, though. According to UW-Madison seniors Azaria Posik and TJ Matzen, who book, blog and promote for Wisconsin Union Directorate’s music committee, EDM’s popularity among college students relates to the scene’s inclusiveness. There’s no need to memorize lyrics or wow others with band trivia, which makes it easy to invite large groups of friends to the show.

“My girlfriend and her roommate, if they hear that an act is good to dance to, they’ll go to the show in a big group,” Matzen says. “The electronic scene is more welcoming and more about letting loose than the indie rock scene.”

Adds Posik: “Word of mouth can be really powerful for these shows. People text their friends, who text their friends, and then party buses are showing up at the Bassnectar show.”

Recession-friendly jams

DJ and promoter Agard says live EDM’s popularity stems from booking decisions clubs made to weather the recession. “The downfall of the economy made it expensive to book bands, so clubs started booking more DJs because DJs have a higher draw per dollar spent,” he says.

Some club owners got acquainted with EDM artists at festivals like Bonnaroo and 10,000 Lakes. “Artists like Bassnectar performed at these festivals back in 2005 or 2006, but they weren’t headlining then,” Agard explains. “They were playing the afterparties, which is how a lot of promoters got hooked on them — and trends like dubstep.”

Take Majestic Theatre co-owner Matt Gerding. Despite being a rock enthusiast, he couldn’t help but notice that Deadmau5 and Bassnectar were climbing the ranks at Lollapalooza.

Now Gerding books many of the area’s big EDM shows, including 18-and-up performances at the Orpheum and the Alliant. Riding the EDM wave has been exciting, he says, because it’s uncharted territory for the Majestic team. Booking the shows has meant making some potentially costly decisions about bumping acts like Deadmau5 and Bassnectar to the Alliant.

“Moving a show to a larger venue, that’s a decision made mostly by the artist’s agent, manager or record label, when tickets are moving at a speedy clip,” he says.

The risk has paid off, and several EDM artists now visit Madison twice a year rather than once. This is good news for venue owners, but it can mean slow nights for local performers who draw some of the same crowd.

Still, fans miss out when they trade local events for the lasers and costumes of touring acts, according to local DJ Josh Landowski, a.k.a. Landology. It is, he notes, impossible for an artist to tailor a set to a crowd of thousands. “At somewhere like the Alliant, you know your set ahead of time,” he says. “You’re feeding off the crowd’s energy, but it’s more about you than them. You almost have to be over-the-top, so people will pay to see you again.”

So fans seeking to lose themselves in a sea of revelers can go to one of the giant arena dance parties. But they should hit up a local event for some personal attention. If you’re a DJ playing a club or restaurant around town, says Landowski, “you focus on even the smallest reactions from the crowd.”

Tuva is a Siberian republic surrounded by two majestic mountain ranges and peppered with tiny deserts, lush valleys, and more than 9,000 rivers. Population-wise, it’s about the size of Iceland and shares a similar history of being isolated from much of the world for thousands of years due to its location and chilly temperatures. Music-wise, it’s one of the most amazing places you’re likely to discover.

Much like the home of Björk and Sigur Rós, Tuva is immersed in a musical tradition that’s deeper than its permafrost. This tradition revolves around throat singing, an art form in which multiple voices seem to spring from one vocalist thanks to the magic of harmonics and overtones.

Scientifically speaking, a singer can amplify different parts of a sound wave by changing the shape of various cavities of the mouth, voice box, and throat, allowing sounds that are subdued in most vocal performances to take center-stage. The result is a sound that’s been described as a “one-man quartet” and even a “bullfrog swallowing a whistle,” as the 1999 documentary film Genghis Blues puts it.

The Alash ensemble, a quartet composed of Bady-Dorzhu Ondar, Ayan-ool Sam, Ayan Shirizhik, and Nachyn Choodu — four twenty-somethings trained in this ancient art by their parents, grandparents, and a healthy dose of intuition — serves as Tuva’s musical ambassador to the United States.

“Things like Jimi Hendrix and the [Sun Ra] Arkestra are slowly but surely having an effect on our music; it’s not so much about directly mixing these artists’ sounds with throat singing but how it affects the way their music feels.”

Over the past three years, the group has performed with the Sun Ra Arkestra, recorded a Christmas album (Jingle All The Way) with Béla Fleck and the Flecktones, and introduced numerous students to a style of music that sounds like a mix between Tom Waits and a flock of swallows.

The band’s flagship song, “Alash,” with its bouncy melody, could be a tune from the Appalachian Mountains or the hills of Ireland. At other times, the group’s sound is more abstract, reminiscent of distant trains, or the yip-yipping martians from Sesame Street.

The music inspires comparisons to nature and the great beyond. Alash is named after one of the most majestic rivers in Tuva, symbolizing the band’s connection to the water from which its ancestors drank thousands of years ago. And just like the movement of water from clouds to streams to lips and back again, Tuvan songs pass from the spirits of nature to the souls of humans, released back into nature via the lips of throat singers.

Though many of Alash’s melodies have cycled through Tuva for centuries, the way the group presents them to the cosmos is very new.

“Things like Jimi Hendrix and the [Sun Ra] Arkestra are slowly but surely having an effect on our music; it’s not so much about directly mixing these artists’ sounds with throat singing, but how it affects the way their music feels,” the band says, via manager and translator Sean Quirk. “We have a new song about reindeer herding. Even though the piece focuses on this practice that’s very much about Tuva, you can sense these other influences if you’re listening closely.”

This is a huge breakthrough for a musical tradition that still considers stringed and woodwind instruments new additions. These instruments include the igil, a two-stringed instrument that’s played like a cello; the doshpuluur, a three-stringed instrument that’s plucked or strummed like a banjo; the byzaanchy, which has four strings that represent the udders of a cow and are “milked” to create a sound; the chadagan, which resembles a zither or a koto; a jaw harp known as a xomus; the murgu and limpi, two types of flutes; and a large drum called a kengirge, which often comes with a set of reindeer bells.

Alash uses all of these instruments and a few others to create a sound that’s lush and layered, with rhythms that duel one moment and collaborate the next. And unlike most bands, Alash will even teach you how to play the instruments — as well as how to build a yurt and cook up some Tuvan snacks — at its concerts, if you have the time and the money. It’s all part of an effort to welcome people from other cultures — especially Americans — into the fold.

“The touring is all about creating a good impression of Tuva and conveying something about the lives of people who live there,” Quirk says, “and maybe attracting a few visitors. Tuva loves guests.”

It’s also a way of bringing bits of the West back to Tuva, which still shows relatively few signs of capitalism. Though many Tuvans descended from nomadic tribes, they are not immune to pangs of homesickness.

When traveling the roads of Texas and Oklahoma, the lonesome cowboy is one American figure Alash can relate to, but not for his cigarettes. It’s because he also feels incomplete without his trusty steed. To keep spirits high, the band adopted a wrangler look — ten-gallon hats and all — when traveling through Texas, stopping in Fort Worth to ride a mechanical bull and visit some friends with a horse ranch.

“Like many people from Tuva, they feel most at home when riding their horses,” Quirk says.

Composer John Cage, the man responsible for the world’s first song that consisted entirely of a man sitting idly in front of a piano, adored randomness in its many forms. So did choreographer Merce Cunningham, one of Cage’s most important collaborators and his longtime boyfriend. Though both men were pioneers of avant-garde art and teachers at the super-experimental Black Mountain College (also the home of artists Josef and Anni Albers, Willem De Kooning, and Robert Motherwell), neither focused on visual art. It’s their shared love of randomness that unites the visual works the Madison Museum Of Contemporary Art has assembled in Cage And Cunningham: Chance, Time, And Concept In The Visual Arts, on display through May 9.

A lack of structure and formality becomes the show’s common thread, forging connections among pieces from the Bauhaus school, the conceptual art movement, and the ’60s “happenings” of the New York City counterculture. It’s not always clear how exactly the works should be associated with Cage or Cunningham (with some exceptions); perhaps the show’s curator wanted it that way.

Sol LeWitt’s 1991 etching “Vertical Not Straight Lines Not Touching On Color” consists—surprise, surprise—of a smattering of white vertical lines, some more squiggly than straight, on a black rectangle of background. Each line is pencil-thin and hairlike, and several of them veer so close to one another that they appear to touch, despite what the museum’s notes about the piece say. As the title suggests, this piece is more about absence than presence. LeWitt’s idea becomes more important than the execution of his idea, illustrating what conceptual art is about.

Cage And Cunninghan also offers a roadmap for understanding how things such as noise and found sounds have become the musical staples they are today. Two pieces by George Maciunas show how the multimedia Fluxus movement of the ’60s, a precursor to the modern noise-music craze, among other things, used games and chance to create a new set of rules for art and music. “Single Card Flux Deck” displays a deck of 52 cards, all of which are spades. Three sets of four tens are turned up, as if to illustrate a winning hand in a game from another culture—or another dimension. It’s as simple as it is mind-boggling.

“Fluxshop Sheet,” on the other hand, is both a game and an advertisement for one. A poster made of black ink on old, yellowing paper that gives it an old-timey feel, like a wanted poster in a saloon, it contains two blocks of text, one horizontal and the other vertical, that spell out a manifesto (or something like one) for such Fluxus artists as Yoko Ono, Ay-O and George Brecht. It spouts activist terms like “nonprofit” and “nonparasitic” while an old-timey cartoon character entices viewers with “games, gags, jokes, kits.” Sixteen faces at the bottom of the piece hold letters on their tongues (or perhaps their chins) that spell “flux orchestra.” It’s yet another example of how Cage and his followers blurred the lines that separate literature, visual art, and music.

“Weather-ed II,” a color photoetching by Cage himself, ventures into the territory of meteorology. With abstract lines rendered in grays, blues and purples, he doesn’t examine the raindrops and lightning but the randomness of weather patterns, from the way they take shape to the way we interpret them. These lines are framed by two boxes that function as windows for watching one storm happen and another one brew. At the same time, they’re a bit like music players as well, with Cage’s lines forming shapes that look suspiciously similar to sound waves. Perhaps this is a chance resemblance, but if so, it’s one he would probably have appreciated.

It was one of the coldest nights of winter 2009, but the Wisco was sweltering with rock ‘n’ roll. The Goodnight Loving were in from Milwaukee, Screamin’ Cyn Cyn & the Pons were in top form, and the Midwest Beat’s Matt Joyce did a scorching solo set. The only band I’d missed was the Hussy. I’d caught the tail end of their set on three different occasions and was hoping this night would be different.

Frustrated, I stomped down the steps, ready to kick the nearest snow bank. That’s when I saw it: a Hussy T-shirt, just my size, drenched in sweat. I almost needed an ice pick to remove it from the sidewalk, but after that, the shirt became my most treasured item of clothing. I wrote in it. I slept in it. I lent it to my friends. The shirt made people laugh, and it started conversations. It got me talking, too, no small feat for someone prone to shyness. Plus, it reminded me to catch the Hussy’s next show — and buy another one of their shirts.

For local musicians, merchandise works magic. Not only does it help fans find one another and show off their taste, it allows Madison bands to take their shows on the road. For groups like All Tiny Creatures and the Pons, merch has funded trips to South by Southwest. For others, it has funded recording time in Seattle and tours of Europe.

Kurt Baker, the Madison native who fronts the Portland, Maine, pop-punk band the Leftovers, says that merch — as it’s universally called — means food, fuel and other necessities to get from one town to the next.

“A lot of bands getting out on the road for the first few times don’t get a door deal or much money from the clubs they’re playing,” he explains. “This is especially true for unsigned bands and those on smaller indie labels. They depend on people buying their merch to pay for gas money, food and motel rooms.”

But that’s just the beginning. More and more bands, it seems, are financing their careers with merch rather than mp3s. Irving Azoff, the artist-management magnate who represents Jimmy Buffett and Neil Diamond, explained in a recent New Yorker article that merch sales and third-party sponsorship have virtually replaced record sales in the music industry’s moneymaking model.

This shift has benefited bands such as Massachusetts’ Dropkick Murphys, who reportedly make more from merchandise than recordings. Mike Krol, who drums for Whatfor and Time Since Western and until recently worked for the Madison-based design firm Planet Propaganda, says he’s figured out the secret. He did it by observing one of his best friends, the Murphys’ merch buyer.

“I hung out with him when the Murphys played the Majestic last year, and he literally set up a shopping mall for a merch table,” Krol says. “He does an amazing job with getting the most random merch items: golf balls, bottle openers, Trapper Keepers, key chains, beer koozies, baby bibs, grocery bags.”

Another Madison-bred band Krol sometimes drums for, Sleeping in the Aviary, have adopted an even wackier approach. They’ve been known to peddle clippings of their hair in Ziploc bags and thrift-store coffee mugs decorated with their faces. Krol’s favorite was a huge pair of pink, one-piece pajamas.

Other local groups are upping the ante for creativity and craziness. Masked surf-rockers Knuckel Drager have been making merch awesomeness for years. Darwin Sampson, owner of the Frequency and bassist for Helliphant and Ladybeard, says he’s proud to own one the band’s signature action figures — or fingers, as the case may be. “[It’s] the ‘El Diablo Action Figure,’ which is merely a plastic hand flipping the bird,” he says.

Then there’s the gumball dispenser Knuckel Drager’s Matt Villand unveiled at last month’s Melt-Banana show. “It gave out random objects like vampire teeth and plastic rings,” recalls Knuckel Drager bassist Bill Borowski, who helped open the show with his other band, United Sons of Toil.

More creations by Villand and his bandmates are available through the Black Cat Printing Company, which creates merch items like posters, T-shirts and, yes, gumball machines for other musicians.

Other designers from the area are also using band merch to show off their creative powers. Krol has made baseball jerseys for Icarus Himself, while artists from the recently shuttered art collective Firecracker Studios made hundreds of gig posters over the course of five years. In September, the Project Lodge even hosted an art show of posters custom-made for the Forward Music Festival, submitted by designers from here to Philadelphia.

While a designer can spruce up a band’s merch offerings, lots of bands without design pros are trying their hand at creating stuff, too.

For Shane O’Neill of the Pons, his electro-meets-comedy venture Shane Shane doubles as an outlet for his craft projects. He even runs an Etsy store when he’s not working on lyrics and dance moves.

At Shane Shane shows, O’Neill dresses up as a giant soft-serve cone, then heads to his merch table to distribute free, ice-cream-themed buttons and stickers. This gets people interested in buying his T-shirts, and it gets them talking about the show.

“I treat stickers, CDs, patches and buttons as promotional materials and only charge money for shirts,” he says. “It’s nice to poor people, and I’m hoping it provides free advertising.”

Even venues are getting involved. At the Frequency, a slew of gig posters, most for local bands, covers the stage room from floor to ceiling. Band stickers, ticket stubs and guitar picks adorn the bar.

Sampson says these decorations have provided an instant conversation piece for customers and have given his staff and bandmates a chance to reminisce. Plus, when bands play there, they have a way to leave their mark.

Near the Frequency’s jukebox and Arkanoid machine are glass cases filled with all sorts of kitschy oddities: a can of “meat” sold by the band Human Aftertaste, an autographed photo of Britney Spears a Frequency employee found during Hippie Christmas, a Mozart action figure and much more. These items pay tribute to Madison showgoers’ merch-buying obsessions while mocking them with a smile and a wink.

For fans, there’s fun to be had in building their own shrines of merch. The process breaks down the wall between performer and audience, especially when a merch-table visit leads to a conversation.

Think of a purchase as a way of thanking a band for rocking, says Jake Shut of the local Crustacean music label.

“When a band that was not on my radar leaves my jaw on the ground with an incredible set, I feel the need to buy some merch from them out of gratitude,” he explains. “And when a band like this can give me an experience that’s a vivid reminder of why I’m so obsessed with music, they deserve some more of my money, sort of akin to getting exceptional service at a restaurant and leaving a fatter tip as a result.”

On the flip side, merch tables are a place for musicians to thank fans for coming out to the show. For Jess Northup of Gold and Shooter Grey Suede, two Chicago bands that play Madison regularly, merch tables have taken the form of a bake sale, with brownies and coffee from bandmate Mike McSherry’s bean-roasting business.

There’s an added benefit as well: The more enticing the merch table, the less isolated the band feels, especially if it’s far from home.

“On tour, Gold will put anything on the merch table that seems remotely interesting, like sunglasses from gas stations,” he says. “We also have a fake fur we use as a backdrop. It encourages people to come over and hang out. Touring gets lonely, after all.”

While the fur and snacks give Gold’s table a twisted Cub Scout vibe, Shane O’Neill says his merch peddling is more like going on a date. “You want to treat someone buying your merch as you would someone buying you a drink,” he says. “They’re also buying your time, so be nice to them and make small talk.”

The Leftovers’ Kurt Baker even suggests that bands bring cameras to their merch tables to keep the conversation going after the show’s over.

“Take a picture with your new fans buying your stuff, then post it online and make them feel special,” he says. “It’s all about connecting with people at the shows and being on a personal level with the audience.”

Dressing up the merch is key. Local bands like Zebras and Underculture have used Christmas lights to add flash to their T-shirts and recordings, even in the middle of summer.

Underculture drummer/vocalist Nate Onsrud says the lights aren’t about holiday cheer. They’re about drawing people’s eyes across a crowded room and into a suitcase packed with their newest offerings.

Meanwhile, All Tiny Creatures offer this tip for bands in the merchandising business: Go minimal. “A great merch table isn’t crowded, and everything is clearly labeled,” says Andrew Fitzpatrick, the band’s guitarist.

The right attitude is probably the most important thing, says multi-instrumentalist Thomas Wincek, who’s also a member of Volcano Choir and Collections of Colonies of Bees.

“In the best-case scenario, merchandise can be used to further a connection people may have with a band. In the worst case, it’s used to cash in on an image and seen as almost more important than the experience of the music,” he argues.

No matter what, merch can help musicians express their sense of humor, which helps them with the all-important human touch.

“Why should corporations, banks and dentists have all the fun?” asks Whatfor drummer Mike Krol. “Why can’t a band have their logo on a pencil sharpener?”

It’s easy to equate the term “paper arts” with grade-school crafts such as paper dolls and papier-mâché piñatas. Thankfully, Aries Tjhin’s new exhibition at the Project Lodge, on display through Feb. 20, is designed to put these images through the shredder, both literally and figuratively.

Tjhin, a 2008 graduate of UW-Madison’s printmaking MFA program and a member of the Milwaukee-based White Whale Collective, carves miniature murals out of paper and cardboard. The process is a meticulous one that involves a steady kitchen table and some impressive skill with an X-Acto knife. From afar, many of the pieces resemble collages of paper doilies and snowflakes, but up close the dark truth comes out: They’re hacked-apart pieces of fairy tales and children’s storybooks, deconstructed, rearranged, and butched up with spray paint.

“The show is about stories—and different kinds of stories—especially stories I’ve read throughout childhood and that flash through my head at these really random times,” says Tjhin. “The way the pieces are made forces you to look at the stories in detail and study the nuances of how they’re made.”

The centerpiece of the installation—a long, horizontal piece called “Hieroglyphics”—fills the gallery’s west wall with glimpses of African folk tales. Familiar figures such as jungle monkeys and a guy who just might be Anansi The Trickster peek out from from a lattice of carved leaves and feathers, vanish into a haze of geometric abstraction, then re-appear in different forms throughout the piece. Some areas of the composition are made entirely of black paper, while others incorporate layers of cardboard and paint, suggesting the many voices and layers that go into the telling and retelling of a story.

Across the room, a piece titled “Door” acts as a portal to an imaginary landscape of horses, clouds, and ninja-like figures that are strung together with a vine straight out of Jack And The Beanstalk. A more abstract piece called “Untitled Yellow” seems like the introduction to a storytelling session—the kind that begins with the incantation “It was a dark and stormy night.” A sky of precisely carved shapes, dusted with tiny yellow paint drops, seems to be breaking apart on a misty evening. Whether it’s a hopeful or ominous story is up for debate: The clouds and stars have been sliced apart and collaged, as if the world is taking a new shape—or history is caving in on itself.

Jazz is playing, the sky is dark, and a bright yellow taxi pulls up outside Parthenon Gyros on State Street. “Y’know, I don’t know much about politics. All I know is that we just need a good, hard rain to wash the scum off the streets,” says the man behind the wheel.

It’s not the beginning of Taxi Driver. The man uttering those words isn’t Robert De Niro. He’s Fred Schepartz, local writer by day and driver with Union Cab of Madison Cooperative by night. And the scene is from “You Talkin’ to Me?” — Commie Taxi Drivers in Wisconsin, a DVD extra for Michael Moore’s latest film, Capitalism: A Love Story.

While Commie Taxi Drivers sprang from Moore’s imagination, there’s plenty of creativity inside those yellow cabs. Schepartz is a great example. When he’s not writing books, such as his 2007 novel Vampire Cabbie, he’s taking photographs and editing Mobius, a journal dedicated to literature, poetry and social change.

Without Union, this trifecta of creative output might not be possible. It’s hard to survive as a novelist if you’ve never published a book, and this was Schepartz’s situation for two decades. To pay the rent after college, Schepartz tried secretarial work and furniture sales, only to find himself with a pink slip — not a book deal — a few years later.

Then he heard about Union, a local, worker-owned cooperative brimming with artists, musicians and writers. Twenty-two years and several novels later, he’s still driving for Union. Like many fellow drivers, he’s discovered that you don’t need an MFA degree to make art, and that creativity and cab driving go hand in hand.

Of course, this combination doesn’t work for everyone. Cab driving in Madison requires a high tolerance for drunk people and the ability to stay cool when other drivers are texting and tailgating on the Beltline.

Plus, not every cab company offers a structure or vision like Union’s. Its mission statement includes a commitment to paying workers a living wage, whether they drive cabs, crunch numbers or clean toilets. For drivers, pay is based on a commission that’s a percentage of customer fees. The more hours drivers log, the bigger cut they get.

“Over the last 30 years or so, median wages for most working Americans have dropped, but the way Union Cab is set up, your real wage actually increases. And this helps the artistic life if you don’t have to work 60, 80 or 100 hours a week just to eke out a living,” Schepartz says. “And when you leave your shift, you don’t take your work home with you. To make art, you need a lot of time to think.”

Culture club

For Union Cab drivers, contemplation can even happen on the job, while waiting at an airport or a stoplight. For Mark Adkins, leader of Subvocal, a psych-folk band formed at Union Cab, an epiphany at the corner of State and Gilman streets led to one of his most memorable songs, “11303.”

“I saw this student walking by who was very pretty, except her nose was missing. I wondered how she dealt with her lot in life, and I began thinking about how people wear these different masks,” he recalls. “I came up with the song’s first line, ‘I see nothing but sorrow walking down the street,’ and I realized I was writing down feelings about my brother, who’d recently committed suicide. It was a real turning point.”

The album containing “11303,” Nikkis Room, was a turning point as well, winning Subvocal the 2005 Madison Area Music Award for best CD.

Good pay and ample downtime aren’t the only reasons creative people flock to Union. The co-op takes pride in its nontraditional philosophy about work. As a result, its culture isn’t typical.

“People are exactly who they say they are there, and it’s a very comfortable place to work because you don’t have to worry about what other people think,” says Jai Ingersoll, Union alum and vocalist for local goth-tronica group Sensuous Enemy. “I have tattoos and piercings and red hair, but it didn’t matter there. A lot of other places it would.”

Plus, if you talk to Union drivers at length, you’re likely to hear them refer to fellow worker-owners as family, not coworkers. As Adkins puts it, “We’re all writers and musicians and politicos, rebels and radicals and misfits. But even those of us with crappy attitudes will still get out of the car to fix your flat on a snowy day.”

This isn’t because Union workers are more compassionate than others; it’s a function of an environment that eschews competition and promotes empowerment, Adkins says. This type of atmosphere can also help talented people truly pursue their gifts, whether it’s music, metalworking or mime.

John McNamara, the co-op’s marketing manager, says a humane work environment simply encourages people to do their very best, whether it’s in the office, in a cab or at their after-work pursuits.

“We want people to like coming to work, not feel chewed up and spit out, which is the case at many companies. And because of the camaraderie that exists here, there’s a natural tendency to share and collaborate,” he says. “We work on teams and solve problems together. There’s not a lot of selfishness here, and that way of doing things spills over into other parts of people’s lives.”

McNamara credits much of this outlook to the zeitgeist of the 1970s, when Madison flexed its creative muscles in unprecedented ways. “People were really questioning the status quo and coming up with positive ways of changing the world,” he says. “The Union Cab people were part of this, along with WORT, the Willy Street Co-op, the Mifflin Street Co-op and Commonwealth Development.”

Problems plaguing the cab industry were troubling for drivers and consumers alike, he adds.

“Everything was being done on the cheap back then. Vehicles were unsafe, and drivers were very poorly paid. That translated into poor morale and poor customer service.” And that’s one thing Union’s founders set out to change.

Creative folks soon caught wind of the co-op’s flexible schedules, which could easily accommodate a band’s cross-country tour or a two-month writing sabbatical, and began to fill the Union’s ranks. Pretty soon, Butch Vig, who would go on to found Smart Studios and the band Garbage, was driving a Union cab. So was Michael Feldman, who now hosts the comedy and quiz show Whad’Ya Know?, which is heard on public radio stations across the country. Local author and historian Stu Levitan and Latin-jazz icon Tony Castañeda followed, along with many others.

Feldman, who drove for Union from 1981 to 1983, after quitting his first radio show, says unemployment led him to the co-op, along with its reputation for hiring creative individuals.

“They were hiring people like actor cab drivers and writer cab drivers, and they took me because I was a minor celebrity. They thought it would be good for business, but I was a terrible cab driver.”

Though Feldman doubted his cabbie skills, the gig led to something useful: a new public radio show. “We taped radio bits in the cabs and called it The Dispatcher,” he says. As a dispatcher wrangled cabs, “I’d be trying to break in with a question, like ‘What caused the extinction of the dinosaurs?’ We’d tape that and put it on the air.”

Rearview visionaries

Since Union has more than 200 employees, chances are good that an artsy new hire will already know a few other workers from gallery night or the local concert scene. Once these folks find each other, collaboration ensues.

Take longtime cabbie Kelly Burns Gray. A visual artist, she made sure a new CD of music by Union employees past and present came to be. Some of this do-good spirit stems from her personality, but another motivation is thanking Castañeda, who mentored her on some of her first drives.

“One of the things he trained me on was how to hold a coffee cup between my legs and use my lap as a plate. That experience sealed the deal,” she recalls.

Gray had watched Adkins put together Rearview Visionaries, a disc of Union cabbies’ original music, in 2002, so she knew the project could be done if she connected with the right people. With songs by Model Citizen, Wayside, Subvocal and others, the album’s still talked about among cabbies, and many seemed eager to create a follow-up. According to Steve Pingry, cellist for Subvocal and the Getaway Drivers, the original idea was to create a Rearview Visionaries boxed set, so a second CD would mean that the project was two-thirds complete.

After soliciting submissions on Facebook and through the grapevine, Gray got in touch with local musician and fellow cabbie Lonnie Wild, who paid for duplication of the new CD. Meanwhile, Smart Studios’ Mike Zirkel volunteered to master it. The final product debuted in January, featuring tracks by Sensuous Enemy, the Stellanovas, the Getaway Drivers, Castañeda and many others. In addition to spinning in many cabbies’ cars, it won a Madison Area Music Award this spring.

Meanwhile, Kristin Forde, a visual artist, theater person and Union cabbie of six years, has been organizing art shows with a purpose similar to the CDs’: to highlight the co-op’s creative talent. The first show, featuring political posters, photography, blown-glass mixed-media pieces and more by 10 Union Cab artists, took place last summer at the Gallery at Yahara Bay Distillery. Another will take place at the gallery July 29 through Sept. 24 of this year, with an opening reception July 30.

Forde, a former middle school teacher, credits cab driving for sparking a personal artistic awakening, so organizing a show is the least she can do to give back.

“Cab driving has opened up my creative life tremendously,” she says. “There’s something about being in constant motion, with the scenery always changing, that’s important to the photographs I take.”

And this sense of moving forward, making progress toward destinations physical, political, psychological and spiritual, is crucial to what Union stands for. It’s only natural that cabbies show off the values they’ve taught and learned at the co-op.

“The co-op model attracts people who are interested in an alternative way of life, one that’s very participatory and has a strong creative element,” Forde says. “Those of us who work at Union own it, too, so it’s up to us to make sure it remains this unique place that nurtures things the greater society doesn’t always value: individuality, creative expression and, of course, union.”

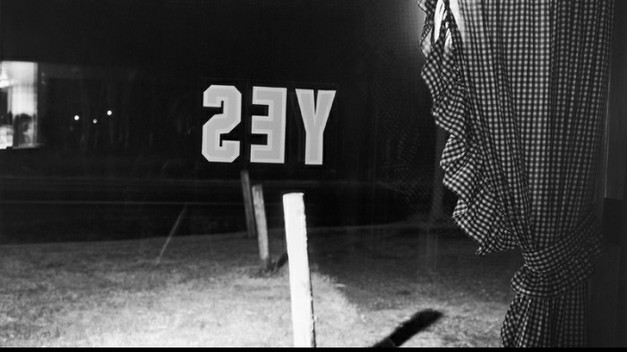

Pieces of text often come disguised as debris–candy wrappers, discarded receipts, fading patches of graffiti–but they’re still saying something. It’s just a question of what. For photographer Lewis Koch (who speaks this Saturday afternoon at Rainbow Bookstore Co-Op), these letters, numbers, and symbols spell out poems. They might not form tidy stanzas or couplets, and they might not rhyme, but they share the spirit of Surrealism that has fascinated poets such as John Ashbery and Allen Ginsberg and free-jazz musicians like Sun Ra. They speak to us in a language that’s alien to our sense of reason, but familiar to our emotions and even our memories.

Koch’s new book, Touchless Automatic Wonder, a collection of what he calls “found text photographs from the real world,” creates a poem that’s both miniature and epic. Though these images contain just a handful of words, they say a lot and ask even more. They also represent nearly three decades of observation and creation by the Madison-based artist, whose work has made its way into the permanent collections of the Whitney and the Metropolitan Museum Of Art and appeared in exhibitions in New York, London, Seoul, and beyond.

The book begins with a black-and-white print of a window, viewed from the inside of a building. Plastered on the glass is the word “yes,” which appears to float above the street outside. A few pages later is a long-division problem, spelled out in sticks–or pretzel sticks, perhaps–on a table peppered with napkins and coffee cups. Other words and letters pop up like guests at a surprise party: The word “dream” (emblazoned on some large, decaying object) hides behind a chalkboard of children’s drawings; a broken record surfaces in a field, among the unruly leaves and flowers. A painting of a lady revealing her garter points at the word “almost,” while a television with a man waving his finger reminds everyone to “wear suspenders,” as if neglecting to do so is a very serious transgression. Meanwhile, a deserted car lot sprouts four signs from its cracked concrete, all of which say “OK,” even though business clearly isn’t booming.

What’s most fascinating about these photos, however, is that they’ll likely mean something different to each person who sees them, dredging up a unique combination of memories and associations. In the introduction to the book, Koch says it’s the images’ fragmented nature that creates a “sometimes deliberate, sometimes accidental account of one’s life.” But rather than reading them like a novel, they can be read like a diary, a riddle, or even a dream.

If the debut LP by Swedish dream-pop duo Korralreven were a dessert, it would be a molecular gastronomist’s version of cotton candy: flash-frozen wisps of spun sugar. The album is the kind of crisp confection that conjures a sense of comfort. Part of the magic stems from the place that inspired it: Samoa, the tropical getaway where Korralreven’s Marcus Joons had a spiritual awakening. An Album is the soundtrack to his epiphany, not just an invitation to chill out.

Guest singer Victoria Bergsman sets the stage with album opener “As Young as Yesterday,” which teems with whispered vocals. The sonic breeze of “Sa Sa Samoa” incorporates joyful noise from an island choir and rattles an assortment of percussion instruments. Throughout the album, the band basks in the power of musical hypnotism, nodding to transcendent 1980s tracks like Peter Gabriel’s “In Your Eyes” on “The Truest Faith.” There are also hints of the early 1990s’ ambient scene in the mesmerizing electronic waves of “A Surf on Endorphins.”

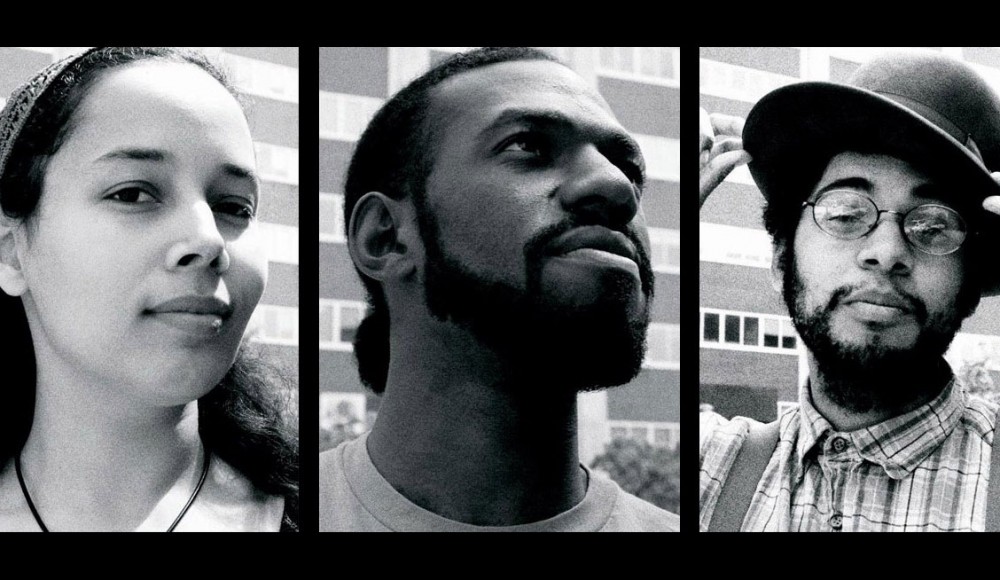

Carolina Chocolate Drops knows a thing or two about blending in. On the cover of the trio’s 2010 album, Genuine Negro Jig, Rhiannon Giddens makes camouflage out of a bright-red dress. Draped on the sofa like a blanket, she matches her surroundings (a red velvet curtain and Oriental rug) so well that she almost disappears. That’s no small feat.

Maybe she’s remembering the old days of the band’s home base of Durham, North Carolina, where until the ’60s, black faces occupied the backs of buses and the margins of their local community, even though they’d created a thriving center of industry, culture, and especially music.

Or maybe she’s channeling the spirit of writer Mary Mebane, who likened her 1930s Durham childhood to an elaborate game of dress-up. Mebane described this Durham as a place where “black skin was to be disguised at all costs” and where those with the darkest faces drowned their insecurities in makeup and whiskey.

Though Appalachian tunes have become the music of all Americans, there’s another truth lurking in the shadows: the story behind the music has been whitewashed.

So perhaps standing out is an even larger feat for Giddens and her bandmates, Dom Flemons and Justin Robinson. They can’t help it, given their musical chops, but they don’t just accept it. They embrace it. And they get their gusto from the ghosts of North Carolina’s past, the black folks who pioneered much of the Appalachian music that launched the careers of white guys like Bela Fleck, the New Lost Ramblers, and the Avett Brothers.

Surprisingly, it was Fleck and the Ramblers who helped Giddens, Flemons, and Robinson find one another at the 2005 Black Banjo Gathering in Boone, NC. The three expected to learn about the instrument’s African and African-American roots, not come away with a globetrotting ensemble and a record deal.

The timing must have been just right. Fleck had recently returned from an African tour, and Mike Seeger of the Ramblers had left New York for a southern sojourn. Flemons traveled all the way from Phoenix just to learn from them. But it was an 86-year-old fiddler named Joe Thompson who sealed the deal, transforming three wandering souls into a tight-knit ensemble.

Now 91, Thompson is thought to be the last living performer from the golden age of Piedmont string bands. In the early 20th Century, he and his family were playing socials and square dances for black and white families alike. At the time, it was one of the rare instances where the racial divide softened, if only for a few hours.

Many people are familiar with the white fiddle-and-banjo music of the southern Appalachian region, but the Piedmont tradition is slightly different. Unlike other Appalachian music, it gives the leading role to the banjo, which sets the tone and tempo of the tunes. The fiddle tends to come second, providing backup along with instruments such as the jug and spoons. This unique combination was pioneered by families of black musicians. Although the banjo was created in the USA, it was inspired by a few lute-like West African instruments. Banjo music was often passed from one black family to the next, and it eventually made its way to other ethnic groups. Until the early 20th Century, young white musicians usually befriended an older black musician if they wanted to learn it.

Learning the banjo also helped the Drops find its identity as a band. Though the group is an old-time string band steeped in Piedmont’s unique blend of folk and blues, it’s a melting pot of other influences as well: some hip hop here, some bluegrass there, with rock and jazz essences filling the gaps. But the three musicians didn’t meld together until Thompson entered the picture.

Somebody had to figure out how to integrate the styles of Giddens, an opera singer with a soft spot for Irish jigs and jazz, with those of Robinson, a classically trained violinist, and Flemons, an Arizona native with a background in folk, jug bands, and old-fashioned country and blues. A Piedmont fiddler through and through, Thompson decided that the best way was to teach them to accompany each other in music and in life.

“We’d go down to his house on Thursday nights and learn how to back him up,” Flemons says. “He’d tell us about some of the older ways of [Southern] living, things like tobacco auctions and frolics, which are square dances in the black community. We really learned about the social functions of the music.”

Pretty soon the band was swapping melodies and instruments, do-si-do style. Now Robinson takes the lead on fiddle, adding banjo, autoharp, and jug as needed, while Flemons lends his skills on various banjos, plus the jug, quills, and harmonica. Giddens plays fiddle, banjo, and kazoo when she’s not wowing the crowd with her vocals.

The audience has added instruments to the lineup too. One fan gave Flemons a set of bones, which also spice up the rhythm of minstrel songs, zydeco, and bluegrass.

“She insisted that I learn how to use them, then showed me how to play them,” he says. “There have been a lot of interesting and wonderful experiences where people have shared songs, instruments, and memories with us. For some reason, our music has opened that up inside of them. Being able to do that is truly amazing.”

Though the group’s goal is to make great music and build a bit of community, it comes with a side of history, especially at its live shows, where Carolina Chocolate Drops is interested in telling the history that history books left out. The trio isn’t breaking out Howard Zinn’s books on stage, but it’s telling it like it is: black people pioneered much of the traditional folk music that spawned country songs. And the banjo wasn’t invented by Bo Duke and The Balladeer. It evolved from several types of African lutes, thanks to the ingenuity of slaves — a fact that banjo players themselves often are surprised to learn.

In other words, though Appalachian tunes have become the music of all Americans, there’s another truth lurking in the shadows: the story behind the music has been whitewashed. We tend to remember the white banjo students but not their black teachers. As a result, much of tradition’s richness is buried, along with the bones of those who played the minstrel shows of the 1880s and the hoedowns of the 1920s and ’30s.

Carolina Chocolate Drops makes music that breaks down cultural barriers and brings together people from various walks of life, but it’s making those black musicians and teachers stick out — in a good way. It’s also helping them gain their rightful place in history and in the imaginations of those listening to the music today.

This theme of rewriting history is heavy one moment and lighthearted the next, much like the songs of Genuine Negro Jig. At least half of the album is good, old-fashioned hoedown fare. There’s hooting and hollering and crazy kazoo solos. There’s more banjo than the Dukes of Hazzard theme song and plenty of material for stomping, swinging, and square dancing.

The other half has some frank messages: advice on how to treat a cheatin’ man and exorcise one’s inner demons. It’s the kind of stuff that gets you talking after passing out from moonshine and dancing. You can’t help but get to know your neighbor.

This is a novel concept for people who spend most of their time on Facebook and iPhones. Yes, the Internet is great at bringing people together, but you can’t dance with it. That’s why Carolina Chocolate Drops blends the whimsy of eras past with the stuff that makes people human today: getting drunk, making out, showing off, and screwing up.

Flemons says that the group marries old and new with the West African concept of Sankofa, which means “go back and fetch it.” It takes good ideas from the past, brings them to the present, and gives them new life.

“We’re not trying to bring the old times back, but we’re using them to help people enjoy themselves,” he says. “Building community by getting people to sing and dance together at a concert makes sense in the modern world.”

But there’s more to it than that. They’re creating something new as well.

Most recently, the music opened the doors of Nonesuch Records, the label that the Magnetic Fields, Brian Wilson, and David Byrne call home. This, in turn, unlocked a Pasadena mansion that once belonged to President Garfield’s widow — and where producer Joe Henry now lives. It was the perfect place to record an album built upon American history.

These sessions led to a haunting rendition of Tom Waits‘ “Trampled Rose” and a fiddle-hop take on Blu Cantrell‘s “Hit ‘Em Up Style.” On the latter, Giddens’ vocals create shivers as she alternately sets the track on fire with her fiddle. Underneath, Flemons’ beat boxing conjures the streets better than a cranked-up bass and a set of chrome rims. Then on the old Charlie Jackson tune “Your Baby Ain’t Sweet Like Mine,” the band traces the blues back to its roots and gives them a Vaudevillian twist, while the Carolinian standard “Trouble in Your Mind” creates the insanity of which it warns with an out-and-out hootenanny. It’s hardly the way to blend in with the crowd.

Flemons says that the album is more of a genre-bender than the band’s earlier releases, but don’t expect Carolina Chocolate Drops to change its tune anytime soon.

“We’re proud to be who we are: an old-time black string band,” he says. “We don’t need to turn into a ’60s girl group or a hair band to stand out.”

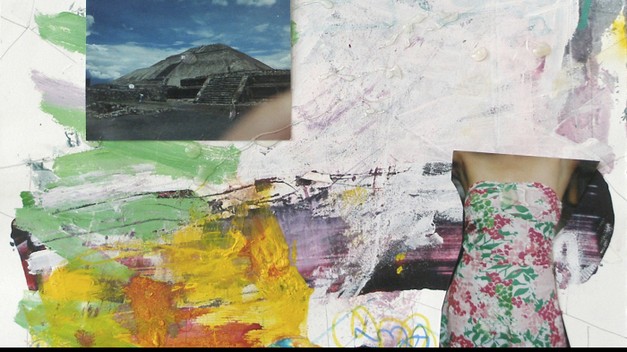

Notes From Places, L.A. artist James Boulton’s show of mixed-media collages on display at Project Lodge through July 9, doesn’t include any written notes whatsoever. There’s nary a title or price in sight, and certainly not an artist’s statement. It’s a refreshing dismissal of the gallery world’s attempt to turn artistic works into retail merchandise that can be compartmentalized and explained.

Boulton uses collage as a code for the tension between order and disorder. His works using paper, many of which were created onsite, are chaotic: sheets of paper splattered with oil paints and images clipped from old magazines and what appear to be found photographs. Yet they are arranged in a precise grid on the Project Lodge’s east and west walls, giving visitors the illusion of safety when they first enter the space.

On closer inspection, it’s clear all this tidy geometry is misleading. In one panel of the grid, a photo of a naked woman splayed on a dirty-looking bed in an even dirtier-looking room floats on a black background, like a character in a video game. Around her are angular shapes that resemble gemstones, rendered in primary colors, along with softer, flower-shaped scribbles. Whether the shapes are out to destroy the woman or help her is debatable.

In another collage (an excerpt is pictured above), Boulton’s scissors have decapitated a photographed woman in a sleeveless dress. A messy square of white paint covers the space where her head should be, and a photo of a mountain—perhaps her last pleasant thought—lingers next to it. An even more puzzling panel features a black-and-white grid within the grid, on top of which orange shapes converge into what looks like a cartoon map. Below, a man in orange hazmat gear is being mauled by a wild animal with a flame bursting from its head. This strange beast isn’t just torturing a human figure, though; it’s also biting the butt of another animal, which is perched atop a huge magazine image of a young girl. Even though this child is the most peaceful character in the scene, she’s also the queen bee since she’s the largest. Underneath her hovers a cutout of children’s underpants and an image of a screaming monkey, adding an extra-absurd twist to the madness. Whatever place this composition is recalling isn’t one you’ll want to visit alone.

Even household objects get twisted and collaged in a collection of cardboard sculptures in the center of the gallery. Each displays a picture of an item you might find at the local Dig ’N Save outlet: a thermos; a broken coffee cup that says “Big Hug Mug”; a creepy, legless Bratz doll; and an upside-down bicycle. Beyond the surface, however, the items from the pictures hide inside the cardboard, as if they’ve transformed from tangible objects into imaginary ones. You could be next.

Many children dream of running off and joining the circus, but only a few brave souls pursue fire eating and tightrope walking as adults. Sleepytime Gorilla Museum has done something even wilder: it has invented its own freak show, something more bizarre and beautiful than any clown-filled big-top.

The fearless five-piece performs one musical stunt after another, bleeding into performance-art territory as it carves genres such as metal, prog, and avant rock into strange new shapes. But this is no novelty act: the group has some substantial — even shocking — things to say about the nature of human life and 21st Century culture.

Most recently, Sleepytime has explored the theme of human extinction, which it began to dissect on its 2004 LP, Of Natural History. Described as a debate between Unabomber Ted Kaczynski and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founder of the Futurist movement, the album seems to boil down to a central question, phrased as a song title: “What shall we do without us?” This question leads to another too: “What might those last days be like?”

“I realized pretty quickly that one of the most direct ways to have a unique, original sound is to play instruments no one else is playing.”

The group’s Fall 2005 tour provided a few answers via Shinichi Iova-Koga, a movement artist who specializes in Butoh, an avant-garde dance form that grew out of student riots and cultural taboos in 1950s Japan. After hanging beneath a sheet, upside down, for the first half of each Sleepytime show, he would emerge as “The Last Human Being,” painted head to toe in white, writhing like a demon-possessed corpse as his shadows danced upon the wall.

These days, the band — clad in tattered tutus, bad-ass boots, and braids — provides a soundtrack for these eerie encounters whether or not Iova-Koga is part of the act. But to take a closer look at this theme of extinction, Sleepytime will soon release a short film called The Last Human Being that explores Iova-Koga’s character while presenting a few new songs.

“During the [2005 tour], we would talk about the human being and what had happened to them, how they used to be all over the place,” says Nils Frykdahl, Sleepytime’s guitar- and flute-playing vocalist. “The film takes that idea even further. It looks like that 1970s TV show In Search of… where Leonard Nimoy was the host and would ‘investigate’ something. We have actors playing a panel of scientists on a talk show. The human is the mysterious creature being ‘investigated.’ It’s fairly comic at its roots.”

Frykdahl says that the film and its music were also inspired, in part, by the story of Ishi, the last of California’s indigenous Yana people. After crossing paths with a group of cattle butchers in 1911, Ishi was quickly put on display at the University of California-Berkeley’s Museum of Anthropology. Though Ishi helped scholars learn about his tribe’s rapidly dying customs and language, he also functioned much like a circus attraction, entertaining guests by making crafts and arrowheads.

“He’s this touching, tragic character,” Frykdahl says. “His life went from a tribal world that was decimated, where he’d seen only a few dozen humans in his entire life and survived, in isolation, in very rough terrain, to suddenly being exposed to Ocean Beach, with thousands of people. He probably stood there with his mouth open, shocked that there were so many human beings in the world.”

Sleepytime taps into this sense of wonder mixed with horror in many of its songs, especially newer offerings like “Salamander.” A mix of apocalyptic sonics — machine-gun drumming, theatrical vocals, commanding rhythms, and loads of distortion — illustrates the struggle to survive in a hostile environment while the band’s absurdist humor seems to mirror the cosmos, laughing at each tiny creature’s fragile existence.

A few tracks from past albums may find their way onto the film’s soundtrack as well. One possibility is “Phthisis,” a song from Of Natural History that imbues Sleepytime’s live act with the essence of an ancient death rite. Beginning with a dose of wailing vocals and metaphorical lyrics from violinist Carla Kihlstedt, the song descends into a primordial ooze of passionate melodies and precise, pounding rhythms. And it’s one of the group’s more straightforward compositions.

Another contender is “The Greenless Wreath,” from the band’s 2007 release, In Glorious Times. Frykdahl’s voice scrapes and scratches like Tom Waits‘ as custom-made instruments create a jungle of futuristic sounds. Built by bassist Dan Rathbun, these instruments create a new lexicon of sounds with which the band can communicate its vision. (Examples include the Pedal-Action Wiggler, a pedal-powered version of the Brazilian berimbau, and the Electric Pancreas, a set of thin metal slices that make a crunching sound when whacked with a stick.)

Then there’s a metal spring, inspired by the one that Einstürzende Neubauten plays in “Selbstportrait mit Kater.” Sleepytime uses it as a percussive instrument and a zany stage prop, along with a bicycle wheel, a kitchen sink, and other found objects.

“Bands like Einstürzende Neubauten — just the number of different things they would make into instruments is inspiring,” Rathbun says. “I realized pretty quickly that one of the most direct ways to have a unique, original sound is to play instruments no one else is playing.”

Frykdahl admits that it’s hard for the band to stick to simple musical concepts — or traditional instrumentation — in its recordings because it has mastered so many daring feats onstage. “Our natural tendency as composers is to fill the space with notes and harmony and melody, which means not leaving room for listening to the noise,” he says. “What we often wish we could do is make beautiful, simple music with a focus on the sound itself, but we like playing notes too much to do that. It seems like the people who do that best are non-musicians who don’t really practice their instruments.”

In other words, Sleepytime isn’t just another prog band with death-metal growls and guitars; it’s an ensemble of classical musicians making high art from unconventional sources. Frykdahl is more likely to gush about modern classical greats Pierre Boulez and György Ligeti than experimental contemporaries Meshuggah and Melt-Banana — when he’s not wrapped up in fairy tales, that is.

Frykdahl, his baby daughter, and Dawn McCarthy—his wife and bandmate in psych-folk project Faun Fables — recently traveled to Idyllwild, California to take in the scenery and make a “fairy-tale rock musical” with a bunch of high-school musicians. Like The Last Human Being, it’s a tale of being left behind. It’s also the perfect story for a tiny hamlet that’s mile high in mountains.

“We arrived with the idea of doing something with the Pied Piper story, where there’s a town that’s infested with rats and the piper leads the rats away,” Frykdahl says. “When the town doesn’t pay the piper, he leads all the children away too, except for this one kid who has a bad foot. That kid doesn’t reach the mountains with the other kids, so he spends his life haunted by what he missed. So, of course, we decided to focus on him.”

The updated fable begins 30 years later than the original, with the bum-footed kid as town mayor. One day, his childhood playmates begin to reappear, as young as the day that they left. Pretty soon the village is filled with orphans, and he must decide what to do with them. According to Frykdahl, using lots of orphan characters makes for lots of acting roles, which allows all of the kids to play themselves—or wilder, more mythical versions of themselves—as they write original songs for the project.

“Right now, we’re madly finishing up parts they can sight-read on French horn and cello, and we may need to do a polyrhythms workshop,” he says, swept up in a flurry of creativity. “But hey, we get to indulge our obsession with fairy tales and mythology, which is really where it all started for us as performers—with cool stories.”

Since forming five years ago, the Minneapolis guitar-and-drums duo Birthday Suits have played hundreds of explosive shows, many in Madison. But until recently, they’d only recorded one other full-length, a mere 15 minutes’ worth of material.

Since forming five years ago, the Minneapolis guitar-and-drums duo Birthday Suits have played hundreds of explosive shows, many in Madison. But until recently, they’d only recorded one other full-length, a mere 15 minutes’ worth of material.

The good news is that their new album is almost 50% longer. This means 50% more fun, lightning-speed rock that bounces from garage to surf to punk-flavored noise and back again. The bad news is that the whole thing’s only 22 minutes long.

“Lost Weekends” shows the band at their spazzy, snazzy best, nodding to the Ramones one moment and No Age the next, while “Kinnickinnic” sounds like a messed-up military march, saluting how fun it is to say the song’s title to the beat of a snare drum. “Miracle Brothers II” throws a wrench into the party, alternating slow-and-sassy thuds with possessed pummeling. And “Rock ‘n Roll Emergency” isn’t just a song but a self-fulfilling prophecy: You’re ridiculously revved up, but the CD’s about to end. It’s your choice: Hit repeat or catch them live, at their brief and beautiful best.

With gargantuan, Steve Urkel-style glasses and an obsession with the bleeps and bloops of computers, Dan Deacon could be the second coming of Revenge of the Nerds’ violin-toting Arnold Poindexter.

Deacon, 27, grew up in the midst of the Long Island ska explosion, performing songs like “Bionic Man Hands” with his band Channel 59. He then went to the local art-nerd institution of choice, SUNY Purchase, to study computer music composition and electro-acoustic instruments. Though Deacon mastered a number of traditional instruments, from guitar to tuba (which he’s played with fellow Purchase alum Langhorne Slim), he chose to record collages of random sounds and sine waves from a Wavetek 180 signal generator.

While his early efforts were more sound art than popular song, Deacon found a fan-friendly formula in his 2007 album Spiderman of the Rings. He mixed goofy-yet-nostalgic lyrics such as “My dad is the coolest dad in dad school / He does not break any dad-rules” with layers of melody that recall Philip Glass. His brand-new album, Bromst, has pleased critics and fans alike, showcasing both his sense of humor and collages of samples that are a bit more grown-up, like a mind-bending round made from a Native American chant.

However, it’s Deacon’s live performances that have made him a household name — if your house is anywhere near an art school or a hipster enclave — by getting disaffected-looking concertgoers to smile genuinely, spill Coke on their vintage pants and abandon their posturing for an entire evening.

How? Deacon’s personality has a lot to do with it. Hooking himself up to a grid of musical machines, he plants himself in the audience and leads fans on a trip that’s as much a spiritual journey as it is a return to grade-school recess. At his Forward Music Fest performance last fall, Deacon invited concertgoers to take part in a Grease-style dance-off to a soundtrack of his tunes. Then the lights went out, Deacon’s LEDs began to blink, and the crowd became a writhing amoeba of sweaty fans simultaneously shouting out lyrics and immersed in their own imaginations. It was as close to a rave as one can get these days, but something else as well.

Viewed from afar — or from above at the Majestic, where he performs May 4 — the scene is performance art, with the audience unaware of its role as performer. That’s the kind of engineering that someone who’s both a math nerd and an art dork could achieve.

“I used to dream of a pirate ship that would take me away from here / out to the open sea, into the biggest blue / complete with a cast of unsavory crew who’d show me things that I shouldn’t do,” sings Rupa Marya, ringleader of Rupa & The April Fishes, on “Wishful Thinking,” the closing track on the band’s 2008 release, eXtraOrdinary rendition.

It’s a fitting manifesto for a band that incorporates all sorts of renegade performance arts — from painting demonstrations to stilt walking — into its live shows, especially in its home base of San Francisco. “We live in an amazing community of artists where someone will just call up the night before a show and say, ‘Hey, do you mind if I play my accordion on the street outside?’” Marya says. “Each show ends up being different from the next based on the cast of characters.”

It’s a formula — or lack of formula — that helps Rupa & the April Fishes’ core members tap into their juiciest layers of creativity and helps the audience lose its preconceptions of what a concert can be. “For me, [live shows] are about everyone coming together to create something beautiful and otherworldly, to take you somewhere unrecognizable and discombobulate you so you can see things from a fresh perspective again,” Marya says. “Having a bunch of pranksters around to help you do that is really helpful.”

The central set of pranksters includes trumpet, accordion, percussion, and upright bass along with Marya on guitar and lead vocals, sung in Spanish, French, Hindi, and a bit of English. Though each of the Fishes is an accomplished solo musician, they sound their mightiest as a school, shifting seamlessly from an Argentine tango to a French chanson, tied together with vocals that are part Edith Piaf, part Hope Sandoval. This sound, which the band describes as “boundary-smashing global agit-pop,” makes mincemeat out of the artificial divides that maps, languages, and political regimes create.

The Fishes succeed in this mission in part because they know how these boundaries look, smell, taste, and sound. For Marya in particular, much of this knowledge comes from growing up in the midst of cultural collision. Born to Indian parents, she divided her childhood years among California, India, and the south of France. Marya was never able to blend in, whether due to her accent, the color of her skin, or her colorful personality, but she was able to carve out an extremely strong sense of self.

“The lessons I’ve learned from practicing medicine, from the amazing people I care for and work with, cross over into what I’m trying to accomplish with music, and vice versa.”

This process of identity building propelled the group’s 2009 recording, Este Mundo, which is sung almost entirely in Spanish. “All the motion in my life has led me to have more of a sense of home than homeland; I don’t have a strong national identity, but I do have a strong self-identity, with bridges to the many different aspects of who I am,” Marya says. “So the idea of home — what it is and where it’s found — has been a major theme in the music.”

Este Mundo frames these ideas not only as political questions but spiritual ones. And unlike eXtraOrdinary rendition, which has a carnival-meets-cabaret vibe and is sung almost entirely in French, it puts a Latin American spin on this quest for meaning.

Several of the album’s songs draw inspiration from brothel-bred tangos and cumbia, a style that began as a courtship dance among Colombian slaves and evolved into a form of political protest, spreading to Panama, Peru, Mexico, El Salvador, and Argentina, where it was adopted by both slum dwellers and orchestra leaders.

On Este Mundo, these dance rhythms create a mood that’s both romantic and rebellious, fit for dinner, dancing, and a hot-and-heavy discussion about Ché Guevara. Marya likens playing the album to looking through a microscope and a telescope at the same time. “It feels broad yet focused, with more abstract elements and more details at the same time,” she says.

The key to combining these apparent contradictions lies in Marya’s “other” job as a doctor at a San Francisco hospital, where she cares for many undocumented immigrants. Marya’s found that her work as a physician has moved her to help marginalized people find not only a voice but a place to call home.

It has also helped her discover music’s power to incite social change. “I’ll be walking down the hall in the hospital, checking in on each of my patients, and I’ll have a prostitute, a CEO, a law assistant, a student, and an immigrant mother, all within a few feet of each other — something that hardly ever happens outside hospitals,” she says.

“It has fueled something in me that’s constantly asking, ‘What kind of world do we live in?’ and ‘What kind of world do we want to live in?’ The purpose of art, I think, isn’t just to expose what’s there but to look at what you wish the world could be.”

One of those wishes involves healthcare, something that many of her musician colleagues and immigrant patients lack. Marya’s quick to point out that the healthcare system, which is supposed to take care of sick people and prevent healthy people from becoming sick, should not be driven by the rules of the free market.

“People who stand to profit from others’ sickness — the insurance companies, the drug companies — shouldn’t get to decide who gets to have an important operation or an MRI or medication, and they certainly shouldn’t be in the same room where decisions about healthcare reform are being made,” she says.

“America is a very wealthy country that has many resources, but its values are out of whack. Reform has to start with some very basic questions about morals and ethics, especially concerning who gets to allocate resources.”

If power can be shifted away from profit seekers, she says, the picture would look very different — and more people might be able to pursue creative careers such as music.

It’s these “what if” questions that link her own two careers as well. Whereas “what if” can lead to an unforgettable chorus or a mind-bending jam session in music, it can lead to a diagnosis or even the cure to a deadly disease in medicine. And “what if” encapsulates the potential of both fields to improve other people’s lives through caring, dedication, and creativity.

Marya admits that most people wouldn’t attempt to be both a doctor and a full-fledged musician, but she’s made it work by challenging the flack she’s received from both professions and highlighting the common ground they share.

“Both are very much focused on compassion and trying to create something that can help people, whether it’s just expressing hope or giving someone something to hold onto in a difficult period,” she says. “The lessons I’ve learned from practicing medicine, from the amazing people I care for and work with, cross over into what I’m trying to accomplish with music, and vice versa.”

Logistically speaking, Marya’s landed a pretty sweet position that lets her spend large chunks of time away from the hospital, touring and recording. She says that this setup isn’t so much a product of luck but knowing who she is.

“When I got my job at the hospital, I explained to them that I wouldn’t be happy without being able to be a musician too,” she says. “They agreed to let me try it, and they saw that it worked, that I’m invigorated and excited to care for my patients when I return from the road. Without music, I wouldn’t be nearly as good of a doctor, and without medicine, I wouldn’t be nearly as good of a musician.”

It’s possible, of course, that Marya’s some kind of superhuman with endless supplies of energy, patience, and passion — plus a sense of optimism bordering on lunacy. The truth is that she’s not crazy at all. Like many artists, she’s fascinated with the fate that no one can escape: death. The difference is that death motivates her rather than making her want to smoke or drink or shudder beneath a cozy pile of blankets.

“When you see a lot of people die, it gives you a very strong appreciation for life,” she says. “You know that time is going to come when you’re too sick to get out of bed, and for me this means making the most out of the time when I am alive and healthy.”

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. “It’s also a tribute to my patients who have passed,” she explains. “That energy and hunger for life is probably the best thing I can give both my fans and my patients who are fighting to get well.”

The Madison Museum Of Contemporary Art’s Return To Function show, on display through Aug. 23, raises a question that many folks unfamiliar with art-gazing ask: Shouldn’t these so-called works of art do something?

In other words, the show encourages viewers to wonder whether art should move beyond its usual functions—decorating a space and promoting high culture, to name a few—and offer us a tangible service other than simply making us think more (or making other people think that we think more, deeper, and better).

Of course, this is all a bit of a sham, because the aim of these pieces is still to oil people’s mental and psychological axles: While a lamp make out of old kiwi containers can, in fact, light a room, its main function is arguably to make viewers consider the nature of consumption and the many possibilities for recycling and reuse.

You’re not likely to wear Lucy Orta’s “Refuge Wear Habitent” unless you’re shaped like a bloated pyramid: The piece begins as an REI-style windbreaker, complete with a drawstring hood, but takes on the shape of a pup tent rather than a human being. Pockets form the windows and the front zipper is an invitation to explore, perhaps, the wearer’s innards or to take shelter in a space that resembles a womb—one that not only keeps you warm, but repels various forms of precipitation.